Photography as “Right Action”

“A balance must be established between these two worlds: the one inside us and the one outside us. As the result of a constant reciprocal process, both these worlds come to form a single one. And it is this world that we must communicate. But this takes care only of the content of the picture. For me, content cannot be separated from form. By form, I mean the rigorous organization of the interplay of surfaces, lines and values. It is in this organization alone that our conceptions and emotions become concrete and communicable. In photography, visual organization can stem only from a developed instinct.”

– Henri Cartier-Bresson

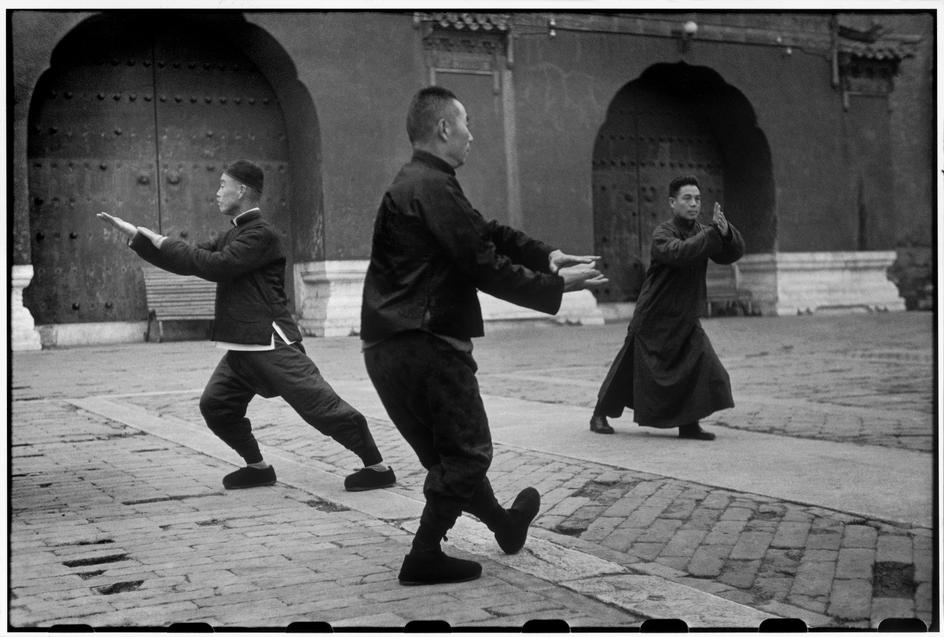

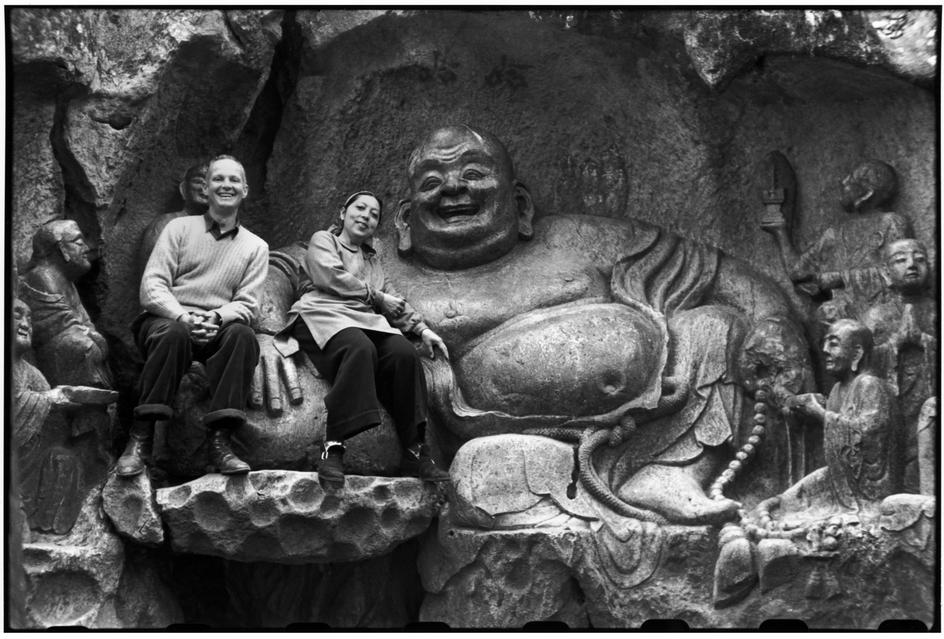

Bresson inspires on so many levels. In viewing his work, I learn about structure, and sight, and time. In his words, I find resonances of Buddhist “Mindfulness,” and a truly conscious appreciation of what it means to be present in the moment. If we read the quote above as referring to samsara and nirvana (the “worlds” of suffering and enlightenment, respectively), another aspect of Bresson’s teachings emerge: his photographs, like Zen paintings, become meditation pieces, inviting us to see past the duality of ordinary perception – and awaken. Apparently, it’s not a stretch to connect HCB with Buddhism. In “The Mind’s Eye” Cartier-Bresson described Buddhism as “neither a religion nor a philosophy, but a medium that consists in controlling the spirit in order to attain harmony, and, through compassion, to offer it to others.” According to the New York Times, he “liked to say that his approach to life had been shaped by Buddhism. His wife, the photographer Martine Franck, described him to the Dalai Lama as ‘a Buddhist in turbulence.’” I like that. Me, too, Henri.

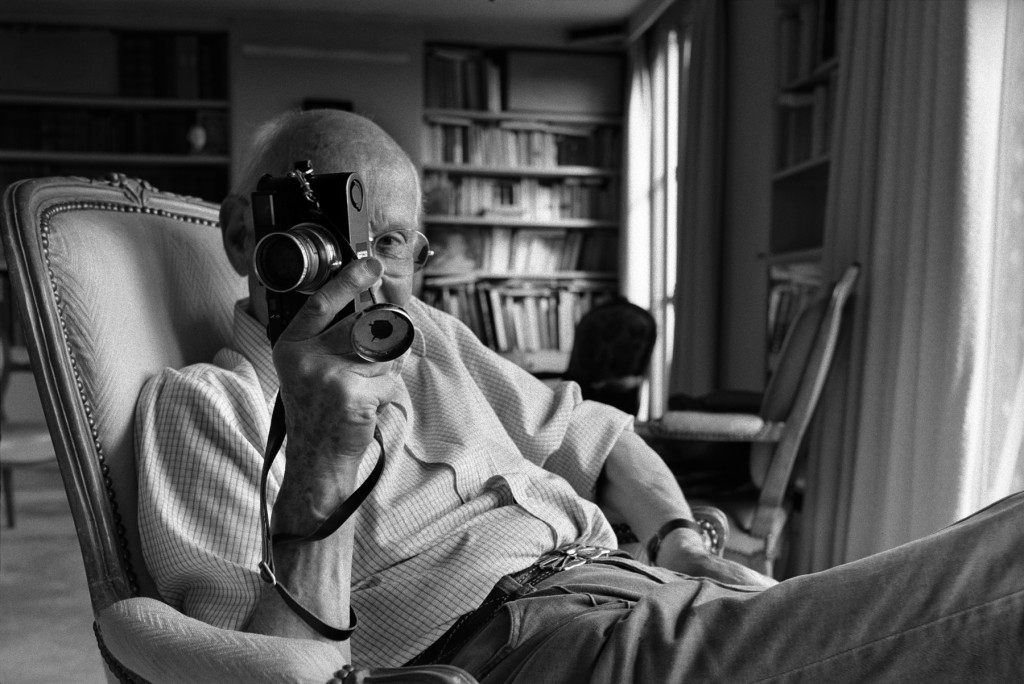

“There’s nobody I admire more in the book. He’s a wonderful man. He was about the age I am now. He was like a tea kettle that is always on simmer. If you said the wrong thing all of a sudden he would start steaming. He had agreed to be photographed, but he wanted to know if all the pictures could be taken from behind. He didn’t like to have his face shown in pictures. His excuse always was that since he worked in the street he didn’t want to be recognized. I have a feeling—and it may be totally unjustified—that he also didn’t like the way he photographed. He wasn’t ever happy with they way he looked, and he found this a very good reason not to be in photos. I was took one shot that focused on his hands, and he said, ‘Oh, don’t focus on my hands, I have arthritis, they look so ugly.’ His hands looked terrific, but he was very self-conscious about it. I think he might have been sorry that he didn’t look like Cary Grant.”

– John Loengard, “The Age of Silver” (interviewed by David Schoenauer)